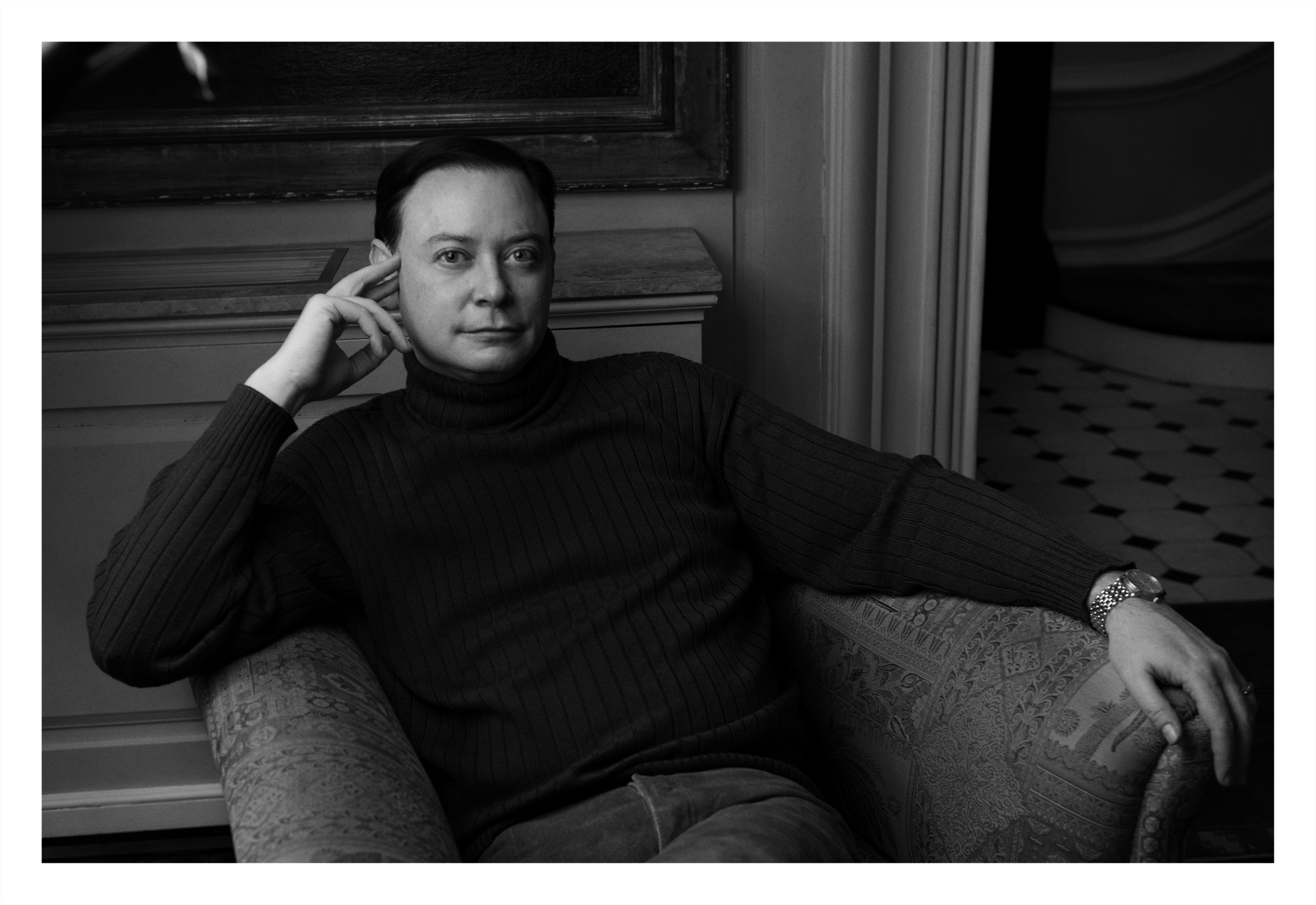

Interviu Andrew Solomon: „Trăiesc bucuria fiecărei dimineţi în care mă trezesc şi nu sunt deprimat, pentru că ştiu cît de groaznică e depresia.”

Scris de Mihaela Butnaru • 5 May 2014 • in categoria Interviuri

Depresia se află în topul problemelor de sănătate pe glob. Totuşi, cu excepţia profesioniştilor şi a celor care au suferit de boală, nimeni nu vrea să vorbească despre depresie. Este o aură întunecată, magică în acest tip de suferinţă inutilă, greu de înţeles dacă nu eşti implicat direct. În mod ironic, depresia are un impact major în sănătate, dar este ascunsă. De aceea consider cărţile precum Demonul amiezii (citește recenzia) un ajutor important în educaţia publicului cu privire la sănătatea mentală. Din păcate, este nevoie de cît mai multe mărturii, cît mai credibile şi mai complexe, pentru ca oamenii să îşi dea seama că depresia nu este un moft, ci o boală gravă. În cele ce urmează, Andrew Solomon, autorul acestei anatomii a depresiei, oferă cîteva idei despre sănătate şi suferinţă.

Depresia se află în topul problemelor de sănătate pe glob. Totuşi, cu excepţia profesioniştilor şi a celor care au suferit de boală, nimeni nu vrea să vorbească despre depresie. Este o aură întunecată, magică în acest tip de suferinţă inutilă, greu de înţeles dacă nu eşti implicat direct. În mod ironic, depresia are un impact major în sănătate, dar este ascunsă. De aceea consider cărţile precum Demonul amiezii (citește recenzia) un ajutor important în educaţia publicului cu privire la sănătatea mentală. Din păcate, este nevoie de cît mai multe mărturii, cît mai credibile şi mai complexe, pentru ca oamenii să îşi dea seama că depresia nu este un moft, ci o boală gravă. În cele ce urmează, Andrew Solomon, autorul acestei anatomii a depresiei, oferă cîteva idei despre sănătate şi suferinţă.

Mihaela Butnaru: Cartea dvs., Demonul amiezii, explorează subiectul depresiei dintr-o perspectivă bazată pe experienţa personală cu boala. Cum aţi descrie depresia pentru o persoană care nu are habar despre subiect?

Andrew Solomon: Opusul depresiei nu este fericirea, ci vitalitatea. Aş spune că depresia constituie o pierdere a energiei, a implicării, o pierdere a voinţei de a trăi. De multe ori spun că dacă sinuciderea ar rezulta din dorinţa pasivă de a nu mai trăi ar fi mult mai multe cazuri; sunt rare pentru că e nevoie de atît de multă muncă [ca să te sinucizi]. Depresia este senzaţia că totul înseamnă un mare efort, că treburile simple – a te da jos din pat, a face un duş, a mînca – par împovărătoare şi copleşitoare. Este o stare care apare adesea împreună cu anxietatea, senzaţia de teamă continuă – starea aceea de o secundă în care aluneci sau te împiedici şi te trezeşti că ai căzut pe jos, doar că în loc să dureze o secundă, durează luni de zile. Este sentimentul de a fi înfricoşat fără să ştii de ce anume îţi este frică. Este lipsa de implicare din propria viaţă, pierderea completă a capacităţii de a simţi plăcere. Este, aşa cum a spus unul dintre intervievaţii mei, un proces în care mori încet.

MB: Ce aţi învăţat din experienţa dvs. referitor la depresie?

AS: Capacitatea de a-ţi tolera propria depresie este, cred eu, ceea ce îţi permite să cîştigi rezilienţă. Prima frază din cartea mea este că depresia este punctul nevralgic al iubirii. Aici cred că se află conexiunea profundă dintre lucruri. Atunci cînd am fost depresiv, am descoperit măsura în care o emoţie te poate copleşi, definind tot ceea ce te înconjoară şi devenind mai reală şi mai clară decît realitatea sau faptele din jur. Această cunoaştere pe care am căpătat-o m-a ajutat să trăiesc şi emoţii pozitive într-o manieră mai intensă şi mai concentrată şi cu o înţelegere mai clară a puterii lor copleşitoare. Trăiesc bucuria fiecărei dimineţi în care mă trezesc şi nu sunt deprimat, pentru că ştiu cît de groaznică e depresia. Chiar dacă acum, într-un fel, nu prea îmi mai amintesc de ea, ştiu că am avut recidive şi ştiu că o să mai am. Cînd mă trezesc şi îmi dau seama că astăzi sunt bine, e un sentiment încîntător. Cred că ceea ce am înţeles din toată povestea asta este că vitalitatea aceea de care m-a privat depresia este ceea ce m-a făcut, cred eu, să trăiesc mai intens. Poate să fie o iluzie pe care o întreţin singur, dar dacă este aşa, este o iluzie foarte productivă pentru mine. Şi asta aş recomanda tuturor.

MB: Ce sfaturi aţi da cuiva care se luptă cu depresia?

AS: Aş sublinia că depresia este o boală care se tratează şi cu cît alegi tratamentul mai devreme, cu atît mai bine. Este mai simplu să-i dai de capăt unei depresii care nu s-a transformat încă într-o criză şi dacă începi lupta mai devreme, ai şanse mai mari de succes. Aş încuraja persoana să înceapă prin reglarea programului de somn şi de nutriţie şi prin evitarea alcoolului şi a cafelei. Aş încuraja-o să facă exerciţii fizice cît de mult poate – activitatea fizică, oricît de ciudat i-ar părea unei persoane deprimate, are un efect aproape la fel de bun ca al medicaţiei. I-aş sugera să evite izolarea; depresia este o boală a singurătăţii, chiar dacă simţi că nu ai chef să vezi pe nimeni, este periculos să rămîi singur. Aş recomanda de asemenea terapia conversaţională şi medicaţia şi subliniez faptul că există doctori buni şi doctori mai puţin buni, iar efortul de a găsi pe cineva competent merită.

MB: Care sunt, în opinia dvs., cele mai întîlnite şi poate cele mai dăunătoare mituri despre depresie?

AS: Cea mai dăunătoare este credinţa că depresia este o slăbiciune de caracter. Dar există şi percepţia că a lupta de unul singur cu depresia este o virtute, ca şi cum dacă ai cere ajutorul nu ai mai ajunge în rai. Depresia este o boală, nu o slăbiciune, iar adesea adevăratul curaj este de a căuta şi găsi ajutor. Eu detest modelul cauzal al depresiei. Depresia poate fi precipitată de un eveniment traumatic, dar nu eşti deprimat pentru că ţi-a falimentat afacerea sau pentru că te-a părăsit nevasta. Din cauza acestor lucruri eşti trist, dar eşti deprimat pentru că creierul tău vulnerabil a transformat tristeţea într-o boală mentală debilitantă.

MB: Care sunt motivele pentru care oamenii evită ajutorul în cazul acestei boli serioase?

AS: Oamenii evită tratamentul pentru că există un stigmat asociat cu depresia. O văd ca pe un eşec, o slăbiciune, nu ca pe o boală. De asemenea, oamenilor le este teamă de tratament. Este aproape imposibil să separi complet boala de personalitate, iar oamenii se tem că tratarea bolii ar implica şi modificarea personalităţii lor. De multe ori trebuie să le amintesc oamenilor că a lua medicamente nu e ca şi cum ţi-ai pierde virginitatea. Dacă încerci medicaţia, îi dai destul timp să acţioneze şi observi că efectele nu sunt bune, poţi oricînd să nu o mai iei. Oamenii nu reuşesc să primească tratament pentru această boală şi pentru că boala în sine îi face să creadă că nimic nu îi poate ajuta. A cere ajutorul înseamnă a fi optimist, iar depresivii chiar nu sunt optimişti.

MB: În România, o problemă a sistemului de sănătate psihică este faptul că oamenii cer ajutorul doar după ce durerea şi suferinţa devin de nesuportat. Care credeţi că sunt motivele pentru care nu se ajunge la ajutor specializat?

AS:Cred că răspunsul este mai sus. Stigmatizarea este enormă, iar campaniile de sănătate publică care i-ar ajuta pe oameni să nu mai fie jenaţi de boala lor ar face mult bine. Dincolo de asta, cred că a admite că primeşti ajutor e o înfrîngere pentru ei, cînd de fapt este singurul mod de a triumfa asupra acestei probleme. Dar problema este mult mai uşor de tratat dacă primeşti ajutor la început, deci a aştepta ca lucrurile să devină catastrofale nu este chiar inteligent.

MB: Sunt surse care indică faptul că schizofrenia este inerentă condiţiei umane, dvs. susţineţi că depresia există atîta timp cît există conştiinţă. Puteţi elabora?

AS: Capacitatea de a simţi este una dintre cele mai importante reuşite ale dezvoltării noastre. Capacitatea de a fi furios, trist, entuziasmat, meditativ sau ursuz, exuberant sau posomorât - nu se poate imagina o fiinţă umană fără stări afective. Atît timp cît avem aceste stări, vor exista şi rateuri în procesele afective. Depresia este o vulnerabilitate care s-a instalat imediat ce am descoperit că avem abilitatea de a experimenta diverse stări de spirit.

MB: Un efect terapeutic se poate regăsi în acceptarea vulnerabilităţii proprii. Este cazul acestei cărţi, v-aţi simţit vulnerabil publicînd-o?

AS: Bineînţeles că m-am simţit vulnerabil publicînd cartea. Am luat acest fapt stigmatizant despre mine, pe care atît de mulţi oameni îl ţin închis bine în ei înşişi, şi l-am difuzat în întreaga lume. M-am simţit vulnerabil la batjocură; am fost vulnerabil cînd mi-am expus sinele în public. Însă din această experienţă am cîştigat şi forţă. Am luat ceea ce am simţit, aşa cum am trăit, ceea ce reprezenta o perioadă inutilă şi golită a vieţii mele şi am transformat-o într-un lucru de valoare. Am răscumpărat timpul pierdut. Nu aş spune că scrisul mi-a atenuat depresia; confesiunile nu rezolvă astfel de probleme. Însă scrisul m-a făcut mai capabil să tolerez acest adevăr despre mine.

MB: Există o variantă de a duce o viaţă bună fiind depresiv? Care este părerea dvs.?

AS: Depresia este o boală epuizantă, iar discreţia, secretul este o întreprindere epuizantă. Primul meu sfat este să recunoşti faţă de tine şi faţă de cei pe care îi iubeşti că ai depresie. Greşeşti dacă ai impresia că nimeni nu te va înţelege; aceasta este o boală care afectează 20% dintre noi în fiecare an, şi mulţi oameni cărora te temi să le spui îţi vor răspunde că şi ei cunosc demonul amiezii. Nu fugi de propria istorie odată ce ai ieşit la suprafaţă. A întoarce spatele experienţei trăite te va face mai vulnerabil faţă de reîntoarcerea ei. Încearcă să incluzi realitatea depresiei în povestea vieţii tale. Dacă o vei vedea ca pe o parte a devenirii tale, vei fi mai bine pregătit pentru următorul atac. Adună cît mai multe experienţe şi trăiri pozitive atunci cînd poţi să o faci, pentru că atunci cînd depresia revine le vei putea scoate la iveală, te vor emoţiona şi te vor ajuta să îţi aminteşti că poţi duce o viaţă bună, că te poţi ridica din starea asta întunecată.

VARIANTA ÎN LIMBA ENGLEZĂ

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. Still, except for the mental health professionals and the ones who suffered from this illness, nobody really wants to talk about depression. It has an aura of magical darkness in its useless suffering, that is hard to understand in the lack of direct involvement. This situation depicts the irony of a disease that has major impact, but remains hidden. This is why I think that books like The Noonday Demon are of great help to educate the general public on the subject of mental health. We need more authentic, complex confessions, so that people understand that depression is a disease, not a frivolity. Below are a few thoughts on health, sanity and suffering from the author of the book, Andrew Solomon.

Mihaela Butnaru: Your book, The Noonday Demon, is an exploration on depression based on a true story – your own experience with this illness. How would you describe depression for someone who has no idea about it?

Andrew Solomon: The opposite of depression is not happiness, but vitality. And I’d say that depression constitutes a loss of energy, a loss of engagement, a loss of the will to live. I often say that if suicide were what came of passively wishing not to be alive, we’d have a great deal more of it; it is rare only because it is so much work. Depression is the feeling that everything is effortful, that the most basic tasks—getting out of bed, taking a shower, eating a meal—seem onerous and overwhelming. It’s a state that often co-occurs with anxiety, the feeling of being afraid all the time, like that second when you slip or trip and feel yourself hurtling toward the floor—but instead of lasting a split second, it lasts for months on end. It’s the sense of being terrified but not knowing what you are afraid of. It’s the disengagement from your own life, the total loss of the ability to feel pleasure in anything. It is, as one of my interview subjects said, a slower way of being dead.

MB: What have you learned from your experience with depression?

AS: That ability to tolerate your own depression is the thing that allows you, I believe, to achieve some resilience. The opening line of my book is that depression is the flaw in love. And I think that there is an incredibly intimate connection between the things. I discovered when I was depressed the extent to which an emotion can take you over and define everything around you and become actually more real and more acute than facts or than reality. That knowledge has allowed me to experience also positive emotion in a more intense and focused way, and with a greater sense of its overwhelming power. I have a sense of joy every day that I wake up and I'm not depressed, because I know how awful it was. And even though at some level now, I can almost not remember it, I know that I've had relapses, and that I will have other relapses. When I wake up and think, oh, I'm fine today, it's thrilling. I think that what I've found out of all of it is that very vitality that the depression at one point robbed me of, and it's caused me, I think, to live more richly. That may be a delusion that I've talked myself into. But if it is, it's been a very productive illusion for me. And it's what I recommend to everyone else.

MB:What advice would you give to someone who is fighting depression?

AS: I’d emphasize that depression is a treatable illness, and that it’s worth seeking treatment sooner rather than later. It’s much easier to turn around a depression before it escalates to crisis, and if you can get started with the fight quickly, you stand a far better chance of success. I’d encourage such a person to start by regularizing sleep and nutrition and by avoiding caffeine and alcohol. I’d encourage such a person to exercise as much as he can bear to; physical activity, which seems like such a really bad idea when you’re depressed, is actually almost as curative as medication. I’d suggest that the person avoid becoming isolated; depression is a disease of loneliness, and even if you feel like you don’t want to see anyone else, it’s dangerous to be alone. And I’d recommend talk therapy and medication, and I’d point out that there are good doctors and indifferent doctors and that it’s worth the effort to find someone truly competent.

MB: What are in your opinion the most common (and maybe damaging) myths about depression?

AS: The most damaging is that depression is a weakness of character. But there is also the perception that there is some virtue in fighting depression “on your own,” as though you were getting demerits in heaven for turning to help. Depression is an illness, not a weakness, and it is often seeking and finding help that constitutes the real courage. I also hate the causal models of depression. Your depression may be triggered by a traumatic event, but you are not depressed because a business venture failed or because your wife left you. You are sad because of those things, but you are depressed because your vulnerable brain has shifted into a debilitating mental illness.

MB: What are the reasons that prevent people from getting help with this serious illness?

AS: People avoid seeking treatment because of the stigma associated with depression. They see it as a weakness, a failing, and not as a disease. Also, people are afraid of treatment. It’s nearly impossible entirely to separate the disease from the personality, and people worry that treating the disease will entail altering their personality. I often have to remind people that taking medication is not like losing your virginity. If you try medication and give it enough time to work and decide you don’t like its effects, then you can always stop taking it. Partly, people fail to get help with this illness because the illness itself makes you think nothing can help. Soliciting help requires optimism, and depressives are not very optimistic.

MB: In Romania, one issue is the mental health field is that people seek an authorized opinion on their suffering only when the pain and damage are unbearable. In your opinion what makes people reluctant to getting professional help?

AS: I think the answer to that is in #5, just above. I think the stigma is enormous, and that public health campaigns to help people be unembarrassed about their condition could do a great deal of good. Beyond that, I think people suppose that getting help is admitting defeat, when in fact it is a mode of triumphing over the problem. But the problem is a lot easier to treat if you get it earlier, and so waiting for things to turn catastrophic is really not very clever.

MB: Some sources indicate that schizophrenia is the inherent disease of human condition, you state that depression exists as long as consciousness exists. Can you elaborate this idea?

AS: The capacity for moods is one of our highest developmental advances. The ability to be angry, or sad, or elated, or pensive, or morose, or exuberant, or gloomy—there can be no imagining human beings without mood. And so long as we have moods, we are going to have misfirings of the mood process. Depression is a vulnerability that set in as soon as we had the capacity for these varied states of mind.

MB: Embracing our vulnerability could have some therapeutic effect. Was it the case with this book? Did you feel vulnerable publishing it?

AS: Of course I felt vulnerable in publishing it. I had taken this stigmatized fact about myself, the one that so many people keep locked tightly away inside themselves, and broadcast it to the world. I felt vulnerable to mockery; I felt vulnerable in having my inner life made into public property. But I also drew strength from the experience. I had taken what felt, as I lived it, like a useless, barren period of my life and I had transformed it into something of lasting value. I had redeemed the lost time. I wouldn’t say that writing about my depression mitigated it; confession does not solve problems like this. But it made me better able to tolerate this fundamental truth about myself.

MB: Is there a formula for living a good life with depression? What are your insights?

AS: Depression is an exhausting disease. And secrecy is an exhausting undertaking. My first advice is to admit the depression to yourself and to the people you love. If you think no one will understand, you are wrong; this is a condition that affects some 20 percent of us in any given year, and many of the people you fear telling will reply that they, too, have known the noonday demon. Don’t run away from your history once you’ve emerged. Turning your back on the experience will only make you more vulnerable to its resurgence. Try to craft a life narrative that incorporates the reality of depression. If you can see it as part of how you came to be yourself, you will be better prepared to weather its next attack. And store up positive experiences when you are feeling well enough to do so, and then you can take them out when depression comes again, and warm yourself by them, and use them to remember that you can have a good life, that you can emerge from this dark state.

Foto: Annie Leibovitz.

cris spune:

6 May 2014 | 9:24 am

sa faci dus, te costa cand sotul plateste factura la apa. si in orasul tau nu ai locuri de munca, sa te duci sa te faci sclav la un sef analfabet. cum sa nu te apuce depresia? romania = tara de rahat. cu ce si unde sa pleci in lume?